With this first song of a tanda, let's look at some of the defining features of Donato in 1942, when the orchestra slows down and sounds ''different'' but is still very much recognizable as Donato. INTRODUCTION TO THIS SERIES: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8A4zv... Link to full, uninterrupted song ''Tu confidencia'': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAnuJ... (Link to the referred, more ''standard'' Donato song from a year earlier: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RJ8i...)

Showing posts with label Tango Music. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tango Music. Show all posts

Sunday, December 4, 2022

Donato in 1942, part 1 of 4: Tu confidencia. A slow, sorrowful, ''odd'' type of Donato :: Lucas Antonisse

With this first song of a tanda, let's look at some of the defining features of Donato in 1942, when the orchestra slows down and sounds ''different'' but is still very much recognizable as Donato. INTRODUCTION TO THIS SERIES: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8A4zv... Link to full, uninterrupted song ''Tu confidencia'': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAnuJ... (Link to the referred, more ''standard'' Donato song from a year earlier: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-RJ8i...)

Qué me has hecho del cariño

Saturday, December 3, 2022

Saturday, September 17, 2022

Insight to Tango - Episode One - Origins of Tango Music

Origins of Argentine Tango music: who actually created it and when? Here are the people and stories.

From ToTango.net - home of the acclaimed tango hits Remasters. http://ToTango.net

Saturday, November 13, 2021

Wednesday, February 6, 2019

My Top 5 Most Played Tango Songs

Based on iTunes play counts...

#1

"Café de los Angelitos", Rodolfo Biagi, Alberto Amor, 06/15/1945

"Cuando Se Ha Querido Mucho"con Jorge Ortiz (also recorded on 06/15/1945) is up there, too, as is "Indiferencia" (09/10/1942) with Jorge Ortiz as well.

#2

"Yo no sé por qué razón", Enrique Rodriguez, Armando Moreno, 05/13/1942

#3

"Verdemar", Carlos diSarli, Oscar Serpa, 09/16/1955

#4

"Nostalgias", Osvaldo Fresedo, Héctor Pacheco, 11/21/1952

#5

"Malena", Anibal Troilo, Raúl Berón, 08/18/1952

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Thursday, March 8, 2018

Ignacio Varchausky :: Estilos Fundamentales de Tango Seminarios

I ran across this on YouTube and created a playlist - somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 or 22 hours of lectures by Ignacio Varchausky on the "fundamental styles of tango". All in Spanish, but no worries for those of us whose Spanish sucks. Click the little gear icon at the lower right of the video screen and turn on the auto-generated Spanish subtitles, let them populate, then click on "auto-translate" and pick your language. It will hesitate for a moment while it's queuing up. Thank God for Google.

Also note that Ignacio is the founder of TangoVia - a non-profit and website which aims at preserving, spreading and developing tango culture throughout the world. Be sure to check out their Tango CD collections, although the Spanish version website is better for this. Looks like you could find them on Amazon, but there are no direct purchase links.

There are also a dozen or so playlists on the Parkinson TeVe YouTube Channel, or click on "Videos" to see everything listed individually. Lots of stuff to watch and listen and ponder and learn here, including various live orchestra performances.

Here are the titles of the videos in the playlist I've created (above):

Pugliese

D'Arienzo

Piazzolla

La Milonga

Laurenz

El o Los Choclos

Calo

Fresedo

Francini-Pontier

De Caro

Elementos Basicos

Gobbi

Salgan

Saturday, January 20, 2018

La Academia Tango Club

Amazing. Huge tango orchestra. Playing La Yumba (Video below the photo.)

http://laacademiatangoclub.com/?lang=en

La Academia Tango Club is a community of orchestras.Over a 100 people group together to learn Tango where it was created. Our orchestras develop professionally with weekly presentations in Buenos Aires and national and international tours. La Academia Tango Club also offers workshops, courses and seminars given by the most important tango musicians.

http://laacademiatangoclub.com/?lang=en

La Academia Tango Club is a community of orchestras.Over a 100 people group together to learn Tango where it was created. Our orchestras develop professionally with weekly presentations in Buenos Aires and national and international tours. La Academia Tango Club also offers workshops, courses and seminars given by the most important tango musicians.

Saturday, May 6, 2017

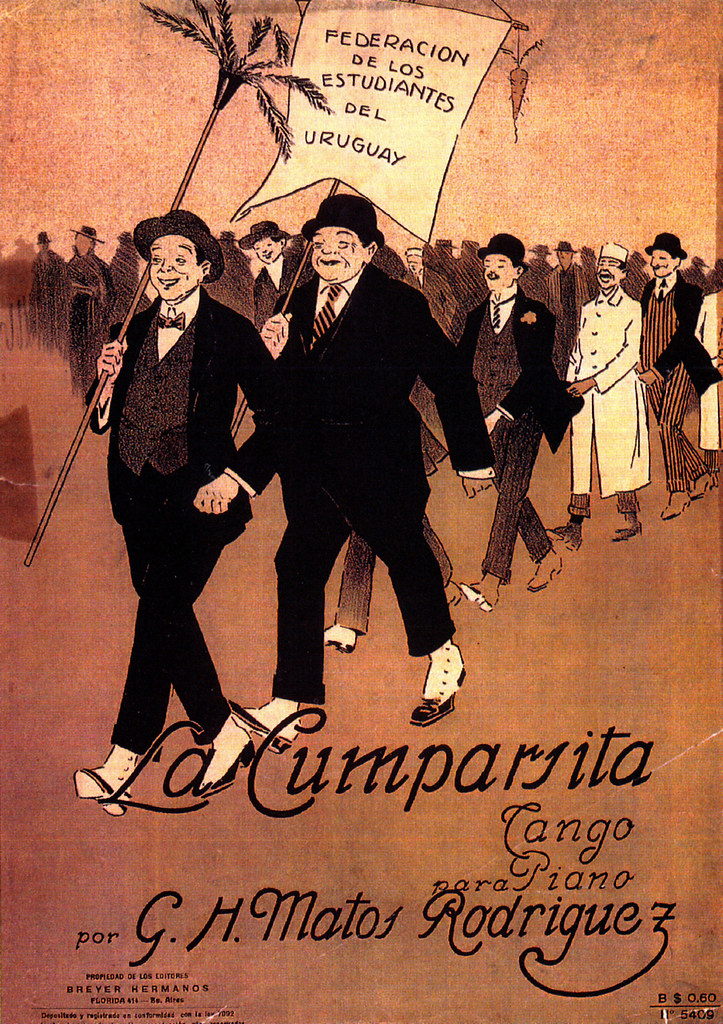

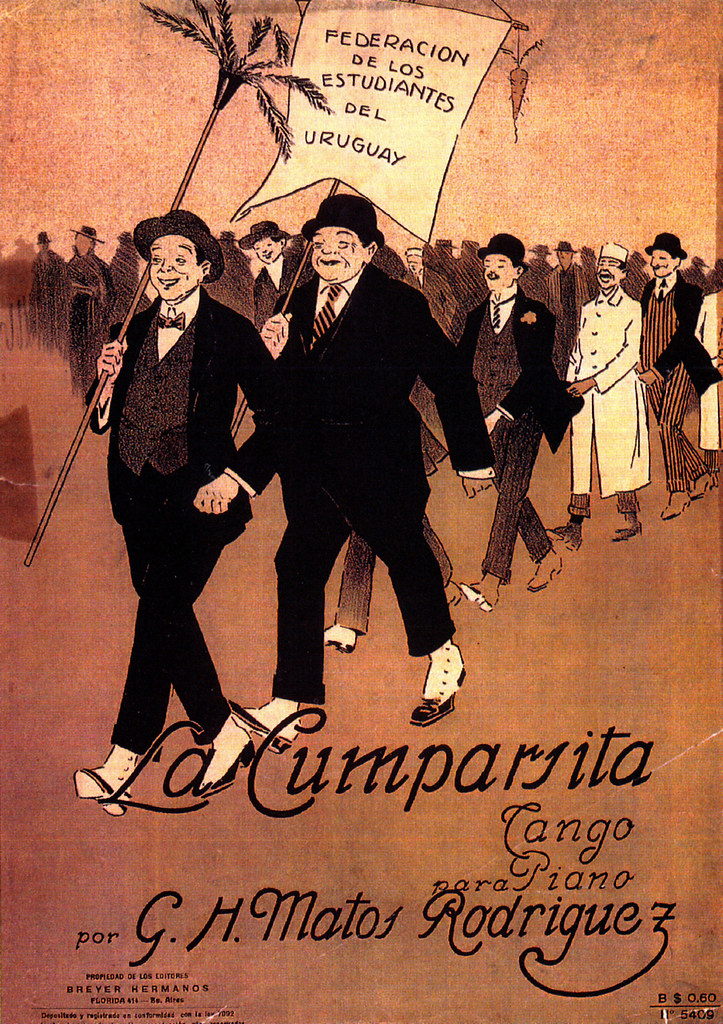

La Cumparsita Redux :: La Ultima Canción :: 100th Anniversary

Note that April 16, 2017 is the 100th Anniversary of the song...

http://www.worldnewsenespanol.com/309_hispanic-world/4507519_uruguay-celebrates-100th-anniversary-of-la-cumparsita-tango.html

http://www.elintransigente.com/espectaculo/musica/2016/8/23/uruguay-quiere-declarar-2017-como-tango-la-cumparsita-398734.html

On the subject of why La Cumparsita is played as the last song at milongas:

This from Glen Royce on Facebook:

Alex: Ahhh- I thought the story was more well-known! :) Pugliese was a communist, and one night the police showed up at the milonga where his orquestra was playing, to bring him in, right when they were playing 'La Cumpa' ...my good tanguero friends down here in BA who are in their 70's and 80's say he WAS arrested, and so the milonga was finished- end of the night! (because the orquestra's director had been taken away...!) Anyway, feel free to read and visit the folllowing : ;)

"Once when Pugliese was playing La Cumparsita, the police entered the club he was performing in, and directed everything to stop as he was banned. The club owners said that they could not be interrupted whilst the orchestra was playing and the dancers was tangoing. On stage, Pugliese was told about this - so started playing La Cumparsita over and over again. The audience just kept on dancing! Eventually the police gave up and left. It was, perhaps, a world record in playing La Cumparsita?"

***Again, I have been told Pugliese DID get arrested and the milonga was finished for the night (no more director OR pianit...!) So that was the last song of the night! :)

And this from Luigi Seta - his blog at: http://tangopills.blogspot.com/2017/04/por-que-la-cumparsita-es-el-ultimo.html

Saturday, April 22, 2017

¿Por qué La Cumparsita es el último tango de la milonga? (Why is La Cumparsita the last tango of the milonga?)

Los milongueros asocian este tango inmortal con Juan D’Arienzo, El Rey del Compás, porque revolucionó todo el mercado con su grabación.

The milongueros associate this immortal tango with Juan D'Arienzo, El Rey del Compás, The King of the Beat, because he revolutionized the whole market with his recording.

Fue además el tema que más veces grabó, hasta en 7 oportunidades. En los años 1928 y 1929, con las voces de Carlos Dante y Raquel Notar, respectivamente, para el sello Electra, propiedad de su tío, Alfredo Améndola. Y luego para el sello Victor en otras cinco placas, en los años 1937, 1943, 1951, 1963 y 1971. La placa de 1951 tenía en la otra faz, la milonga de Pintín Castellanos La Puñalada, que también registró en cuatro ocasiones, y batió records de venta.

It was also the tango that he recorded the most times, up to 7 opportunities. In 1928 and 1929, with the voices of Carlos Dante and Raquel Notar, respectively, for the Electra label, owned by his uncle, Alfredo Améndola. And then for the Victor label on five other records, in 1937, 1943, 1951, 1963 and 1971. The record of 1951 had on the other side, the milonga of Pintín Castellanos La Puñalada, which also recorded four times, to became a sales blockbuster.

La versión de 1951 fue tan famosa, con más de un millón de discos vendidos sólo en Argentina, y más de doscientos mil en Japón, que el público deliraba al escucharla en sus presentaciones en vivo, entonces Juancito decide dejarla siempre para el final de sus shows, como la frutilla del postre.

The 1951 version was so famous, with more than one million albums sold only in Argentina, and more than two hundred thousand in Japan, that the audience raved when listening to it at their live performances, so Juancito decides to leave it always for the end of their Shows, as the icing on the cake.

Y fue así que se impuso como cierre de las milongas a partir de de los años cincuenta en todos los clubes de Buenos Aires. Y quedarse sin bailar este último tango significaba toda una frustración.

And so it was imposed as a closure of the milongas since the fifties in all clubs in Buenos Aires. And then, staying without dancing this last tango meant a whole frustration.

Los muchachos de entonces se reunían para escucharla y también se armaba toda una revolución en las milongas con este tema. Fulvio Salamanca, el pianista de D’Arienzo por 17 años, tuvo especial intervención en los arreglos de esta versión de 1951 y se nota su sabia mano en el resultado final. Una obra maestra y super milonguera.

The guys of the time met to listen to it at home, the streets, everywhere, and then a whole revolution was set up in the milongas with this tango. Fulvio Salamanca, the D'Arienzo pianist for 17 years, had an special intervention in the arrangements of this version of 1951 and it shows his wise hand in the final result. A super milonguera masterpiece.

A continuación La cumparsita por la orquesta de Juan D'Arienzo, en su versión del año 1951, quizás la más famosa de todas.

Next The cumparsita by the orchestra of Juan D'Arienzo, in its version of the year 1951, perhaps the most famous of all.

Presten atención al toque magistral del piano a cargo de Fulvio Salamanca, que le imprimió el clásico compás a la orquesta, una variación moderna y menos eléctrica, que la que le impusiera Rodolfo Biagi.

Pay attention to the masterful touch of the piano by Fulvio Salamanca, who impressed the classic compass to the orchestra, a modern and less electric variation, than that imposed by Rodolfo Biagi.

Escuchen a Enrique Alessio, primer bandoneón, en su famosa variación del segundo coro, magistral, sin palabras.

D'Arienzo, and his line of bandoneons

Junnissi, Lazzari and Alessio

Listen to Enrique Alessio, first bandoneon, in his famous variation of the second choir, masterful, without words.

No dejen de lado la melancolía del final, con el toque impecable del primer violín de la orquesta, Cayetano Puglisi.

Do not leave aside the melancholy of the end, with the impeccable touch of the first violin of the orchestra, Cayetano Puglisi.

Finalmente, la perfecta sincronización instrumental que en corto tiempo le diera a Juan D'Arienzo el acertado calificativo de El Rey del Compás.

Finally, the perfect instrumental synchronization that in a short time gave Juan D'Arienzo the correct qualifier of El Rey del Compás, the King of the Beat.

¡A disfrutar esta joya!

Enjoy this gem!

Here's my prior post:

La Cumparsita is the song that is traditionally the last song played at a milonga. It signals to everyone that this is the last song, and that the milonga has concluded. There was a time when I was on a mission to collect as many versions of the song as I could find. At this point, I have forty [40] distinct versions.

It was written by Gerardo Hernán Matos Rodríguez, an amateur pianist and architecture student, in late 1915 or early 1916 by all accounts. He was 17 years old when he wrote it. It's important to note that he was a student in Montevideo - so the song originated in Uruguay.

The song has a very interesting story behind it - with changed lyrics, new music arrangements, ownership and royalties lawsuits (four or five), and plenty of drama over the years. It's often billed as "the most famous tango in the world". Astor Piazzolla called it "the most frighteningly poor thing in this world" in reference to the original score by Matos Rodríguez and its simple melody.

Here are a couple of links to good, in depth treatments of the song and its history:

Keith Elshaw's www.totango.net

Ricardo García Blaya's www.todotango.com

Note that both of these sites contain a wealth of information about tango music and all things tango.

Alberto Paz' www.planet-tango.com includes a lyrics translation of the re-written version. Alberto's site is well known for his lyrics translations, and also includes a wealth of information about tango.

This 1930 version, with the original lyrics sung by the opera singer Tito Schipa, is my personal favorite.

Lastly, here's a "mashup" of many versions over 26 years...

Saturday, March 11, 2017

The Story Behind Orquesta Típica Victor aka OTV

From Todotango.com

When the officials of that record company had the idea of putting together an orchestra that would represent the corporation, they turned to a pianist classically trained, who had not yet played tango: Adolfo Carabelli.

This great artist studied with the best teachers of his time and when he was fifteen he was already playing concerts in the theaters of the city of Buenos Aires. When he was very young he went to Bologna, where he stayed until 1914. There he went to school and continued his musical studies. When the war broke up he returned to his country where he put together a small group of classical music: Trío Argentina.

Around that time he became acquainted with the pianist Lipoff, who accompanied the well-known dancer Anna Pavlova, and through him he was introduced to jazz, a genre that was beginning to get a wide acclaim.

His first orchestra was named River Jazz Band, later, when switching to the radio, the group bore his name, and the orchestra achieved an overwhelming success and was requested by all the nightclubs of the period. Eduardo Armani and Antonio Pugliese, among others, passed through its ranks.

He recorded his early records for the Electra label and later he is hired by the Victor company as musical advisor and responsible for the creation of a tango orchestra.

It was a seminal orchestra in tango, that never performed in public, but which left for us, during its long career, the indelible memory of its perfection and quality.

The first setting chosen by Carabelli, and that made its debut recording two tangos on November 9, 1925: “Olvido [b]”, by Ángel D'Agostino, and “Sarandí” by Juan Baüer, was the following: Luis Petrucelli, Nicolás Primiani and Ciriaco Ortiz (bandoneons); Manlio Francia, Agesilao Ferrazzano and Eugenio Romano (violins); Vicente Gorrese (piano) and Humberto Costanzo (double bass).

The composition of the orchestra changed very often, the musicians were continuously replaced, but they all were of an excellent level. So that so that some experts recognize, on certain recordings, the violin of Elvino Vardaro, for example.

Other important names that passed through the ranks of the orchestra were: Federico Scorticati, Carlos Marcucci and Pedro Laurenz (bandoneon players); Orlando Carabelli, brother of the leader, and Nerón Ferrazzano (double bass); Nicolás Di Masi, Antonio Buglione, Eduardo Armani and Eugenio Nobile (violins). Cayetano Puglisi, Alfredo De Franco and Aníbal Troilo were also included in the orchestra on some occasions.

Years later, and due to commercial reasons, the label thought that only one orchestra was not enough. For that reason a number of orchestras began to appear: Orquesta Victor Popular, the Orquesta Típica Los Provincianos led by Ciriaco Ortiz, the Orquesta Radio Victor Argentina led by Mario Maurano, the Orquesta Argentina Victor, the Orquesta Victor Internacional, the Cuarteto Victor lined up by Cayetano Puglisi, Antonio Rossi (violins), Ciriaco Ortiz and Francisco Pracánico (bandoneons) and the excellent Trío Victor, with the violinist Elvino Vardaro and the guitarists Oscar Alemán and Gastón Bueno Lobo.

The already mentioned quality of the musicians made the Orquesta Típica Victor one of the highest musical expressions of its period, and it would remain at the same level until the late thirties. And this is important to highlight, because other important orchestras, such as Julio De Caro, had lost their north.

Unfortunately later, because of a repertory that tried to fit into the commercial needs of the period, the quality of it declined, but neither its sound nor the capability of its members were of a poor level. Its vocalists, likewise, kept on being of a first rate level.

In 1936 the leadership of the orchestra is transferred to the bandoneonist Federico Scorticati, and its early recordings were the tangos “Cansancio” (by Federico Scorticati and Manuel Meaños) and “Amargura” (by Carlos Gardel and Alfredo Le Pera), sung by Héctor Palacios.

In 1943 the orchestra was led by the pianist Mario Maurano, and recorded the tangos “Nene caprichoso” and “Tranquilo viejo tranquilo” (both by Francisco Canaro and Ivo Pelay), with Ortega Del Cerro on vocals, on September 2.

The last recordings under the name Orquesta Típica Victor were made on May 9, 1944, and they were the waltzes “Uno que ha sido marino” (by Ulloa Díaz) and the popular “Sobre las olas” (by Juventino Rosas), both sung by the Jaime Moreno and Lito Bayardo duo.

According to Nicolás Lefcovich's discography, the recordings were 444, but to this number we would have to add many recordings coupled on discs that on the opposite face had renditions of varied interpreters.

Even though it was an orchestra that mainly played tango, it also recorded other beats, more than forty rancheras and a similar number of waltzes, around fifteen foxtrots and very few milongas. Also polkas, corridos, pasodobles, etc.

As for vocalists, they appeared only three years after its creation, after over a hundred instrumental numbers were recorded. And the first one was a violinist, Antonio Buglione (a total of four recordings), with the tango "Piba", on October 8, 1928.

He was followed by Roberto Díaz (27 recordings), Carlos Lafuente (37, the one who recorded most), Alberto Gómez (25), Ernesto Famá (17), Luis Díaz (14), Teófilo Ibáñez (9), Ortega Del Cerro (7), Juan Carlos Delson (7), Mario Corrales —later Mario Pomar — (6) and Charlo (4).

Through the ranks of the orchestra the following vocalists passed: Alberto Carol, Jaime Moreno, Lito Bayardo, Lita Morales, Eugenio Viñas, Ángel Vargas, José Bohr, Osvaldo Moreno, Vicente Crisera, Dorita Davis, Oscar Ugarte, Fernando Díaz, Héctor Palacios, Mariano Balcarce, El Príncipe Azul, Francisco Fiorentino, Armando Barbé (also with the name Armando Sentous), Samuel Aguayo, Hugo Gutiérrez, Jimmy People, Deo Costa, Alberto Barros, Raúl Lavalle, Augusto "Tito" Vila and Gino Forsini.

When in 1944 the label decided to put an end to its career, tango was so successful that it would not be an exaggeration to say that everyday a new orchestra was put together. Somehow, with the great orchestras of the forties: Troilo, D'Arienzo, Di Sarli, D'Agostino, Tanturi, Fresedo, Laurenz, among others, the need of having one's own orchestra has come to an end.

From Todotango.com

Thursday, February 9, 2017

Listening to tango dance music - A beginner’s guide - By Michael Lavocah

By

Michael Lavocah

Adapted by the author from Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, 2nd edition, milonga press, 2014.

http://www.milongapress.com/books/tango-stories/english/

Listening to tango dance music - A beginner’s guide

hen listening to tango music for the first time, especially if our main experience of music has been modern pop music, it can be difficult to hear what is going on, and what we hear may well seem like a “wall of sound”. The good news is that listening to music is a faculty that we can develop. Attentive listening immediately changes our experience, making it richer, creating a relationship to the music. If you are a dancer, you dance what you hear, and so what you dance will immediately begin to change as well, without learning any new steps.

1. The four elements

Dance music can be thought of as comprising four elements: beat (compás), rhythm, melody, and lyrics. Lyrics are optional, although there are always feelings. The first step in developing our listening faculty is to learn to listen to these four elements. These form four listening skills, which for the dancer will map to four dancing skills —the skills of dancing to the beat, to the rhythm, to the melody, and to the lyrics—.

Beat and rhythm are not the same. By beat we mean the regular pulse of the music. Beat alone is not music, but it is the foundation of music. We walk on the beats, and so without beat there is no walking dance. Beat is a natural, physical phenomenon, like the beat of your heart, or the cadence of walking, or breathing. Some people think of themselves as having «no sense of rhythm», but the beat is there within us, waiting to be discovered.

Beat and rhythm are connected, and it’s hard to find a tango that is pure beat (i.e. with no rhythmic variation), but there is one: Juan D'Arienzo’s “Nueve de julio” —curiously, and significantly, the breakthrough track for the new D’Arienzo sound— that was created by the arrival of Rodolfo Biagi in 1935.

By rhythm, as distinct from beat, we mean the changing pattern of the beats. A classic example is the opening of “Milongueando en el cuarenta”, recorded by Aníbal Troilo in 1941, with its tumbling syncopation: 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2, 1.

Orquesta Troilo

The melody is what we sing to ourselves, or to others, when we recall a song: the tune. The more romantic orchestras prioritise the melody over the beat and the rhythm. This is something we hear developing in the later recordings of Di Sarli. For an earlier example, we can turn to Lucio Demare’s iconic 1942 recording of “Malena”, his own composition. The melodic line is vigorous and clear, and thus easy to follow.

Finally we have the lyrics – meaning. This element is hidden if we don’t speak Spanish. As an example, let’s take Ada Falcón’s 1940 recording of “Te quiero” (“I love you”) with the orchestra of Francisco Canaro. The opening lines run:

I love you!

As no-one has ever loved you,

and no-one ever will;

I adore you!

As one adores the woman

one has to love…

Hearing these words is sure to change your relationship to the song, and to arouse feelings, perhaps memories, which can then become enfolded into the music and expressed in your dancing.

The tango orchestras mix and prioritise these elements differently and this is one way to feel the orchestras and to distinguish them.

The beat

Beats are not all the same —they have their qualities—, and each orchestra has a different quality to its beat. A first attempt to discern and feel these qualities would be to classify them into polar opposites: hard or soft, strong or weak, sharp and choppy (staccato) or rounded and smooth (legato). D’Arienzo’s beat is staccato, a development that reaches its zenith with Biagi (e.g. the extreme beat of “Racing Club”); whilst Caló’s beat is smooth and soft (“Al compás del corazón (Late un corazón)”). Troilo is more sophisticated, moving between staccato and legato (“Milongueando en el cuarenta”, 1941).

This analysis breaks down when one starts listening to music from before the golden decade. The beats of Roberto Firpo (“La eterna milonga [b]”, 1929) or Juan Maglio (“Sábado ingles”, 1928) are strong, but also soft. In this period, most of the orchestras made a prominent use of the arrastre in their music. Now, what is the arrastre? It is when the beat, instead of being something instantaneous, is made longer, starting quietly and accelerating to a crescendo. In tango, this is described by the sound zhum (written: yum). This effect can be produced on all the instruments within the orchestra. In the bandoneon, it is produced by keying the note before opening the bellows, and then accelerating the opening to a sudden stop: listen for instance to the opening of “Melancólico”. In the strings, the bow is placed on the string before it is moved, and then accelerated. If you are not used to listening for this, it’s easiest to start with the double bass rather than the violins, for instance in the opening of Piazzolla’s “Buenos Aires hora cero”. From the point of view of walking, the most important of the string instruments is the double bass, because it’s the low notes which produce the beats upon which we walk. When going on to listen to the violins, the opening chord of Di Sarli’s “Retirao” provides an exaggerated example.

When the whole orchestra joins in, the effect can be dramatic. My favourite example is a recording by Osvaldo Fresedo’s sextet, “Mamá… cuco” (1927). This reveals another side to Fresedo, full of bite. The arrastre would not be so prominent again until Osvaldo Pugliese incorporated it into what he called la yum-ba: the repeated cell of two strong arrastres (‘yum’) on beats 1 and 3, separated by a less powerful chord on beats 2 and 4 (‘ba’), supported by the double bass powerfully striking the strings with the bow.

The qualities of the beat will affect the quality of the walk. Dancing to different orchestras is not principally about choosing different figures for different kinds of music, although we might: it is about manner. The different qualities of beat inspire different qualities of walking —different ways to place out feet upon the floor—. The arrastre in particular can have a big impact on the way the weight is transferred across the foot.

Rhythm and syncopation

The main rhythmic devices in tango are syncopations —beats falling in unexpected places—.

Let’s start with D’Arienzo. Principally, he uses the syncopa, tango’s classic syncopation – in Western terms, the behind-the-beat syncopation: listen for instance to the first syncopations in “Don Juan (El taita del barrio)” (1936). For a dancer, the staccato acceleration of the syncopa is strongly suggestive of a corte, a cut step. These syncopations often occur in bursts of three —useful information for the dancer—.

Listen closely, and you’ll hear that each syncopation is actually a double syncopation – a behind-the beat syncopation followed by a different one, a before-the-beat syncopation. This is normally much quieter, so we don’t notice it, but when equal prominence is given to both, the result can be disconcerting, as in the opening beats of D’Arienzo’s “Homero” (1937). You can also hear this combination at the opening of all three of Di Sarli’s recordings of “Organito de la tarde”.

Another classic syncopation is the 3-3-2 syncopation (counting 8 beats as 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2). In tango’s golden age, this is found only in the more sophisticated orchestras. Strong examples are Pedro Laurenz’s “Arrabal” (1937) and Troilo’s “Comme il faut” (1938) —both of them electrifying recordings—.

An even more sophisticated and unique example, which we might consider derived from the 3-3-2, is the tumbling syncopation that Troilo employs at the opening of “Milongueando en el cuarenta” (1941). Counting it out, we find that it runs: 3-3-3-3-2-2-1.

The melody

Melody is constructed in phrases, just like human speech. Phrases can be short or long. In the very early days of tango, the days of the 2x4, phrases were always short: think for instance of “El choclo” —but this would soon change—. The example par excellence of the long phrase in tango music occurs in Francisco De Caro’s “Flores negras” (1927), one of the most beautiful melodies ever written in tango. It’s also an excellent example of counterpoint: listen carefully to the opening phrases, and underneath the nasal tones of Julio De Caro’s cornet violin one can hear the second violin playing a completely different tune.

The lyrics

It’s beyond the scope of this essay to talk about lyrics in any depth, but it’s worth noting that in the golden decade, sad lyrics were often given a very bright treatment by the dance orchestras —just think for instance of Troilo’s “Toda mi vida” (1941)—. This creates a bittersweet quality, which is perhaps no accident. If you want to appreciate this, there is no alternative but to learn Spanish.

Mixing the four elements

Generally speaking, dance orchestras lean towards a treatment that favours either the beat and the rhythm (D'Arienzo), or the melody (late Di Sarli). When both aspects are given space, the results are very satisfying: think for instance of Ricardo Tanturi with Enrique Campos, or Ángel D'Agostino with Ángel Vargas.

2. The instruments

Having looked briefly at the way the orchestras treat the elements of beat, rhythm and melody, we can go look at the way they use the instrumental forces at their disposal: the bandoneons, the violins, and the piano. How much prominence is each section given? In the case of the bandoneons and the violins, are individual players given solos? If they are, is there something characteristic about their playing which allows us to enjoy and to identify individual musicians?

The D'Arienzo orchestra always had a terrific bandoneon section, and many pieces culminate in a variación showcasing the ability of the whole group. A classic early example, with very clear phrasing, is the variación in “Paciencia” (1937). Listen closely and you may also hear the delightful changes in rhythm (from 4 beats per note to 3) that D’Arienzo often employs in his variaciones.

The Troilo orchestra has a completely different way of using the bandoneons. Rather than featuring the whole section, Troilo’s solo playing is given space. Troilo was famous for the feeling he put into his playing, and on many occasions he makes music just on a single note: the supreme example is his solo at the end of the milonga “Del tiempo guapo”. His rather more famous solos in “La tablada” (1942) and “La cumparsita” (1944) also use very few notes, but feel more economical and modest, with a subtle, introverted feeling.

Another way of using the bandoneon is shown by fellow bandoneonista Pedro Laurenz. His orchestra makes use of running variations, in which the bandoneon doesn’t pause for breath. The bandoneon is bisonic: each button produces two different notes according to whether the instrument is being opened or closed. It’s easier to play the instrument with power when opening, because, with the help of gravity, the instrument falls open across your knee. For this reason, many players mostly play in the opening direction, and then quickly close the instrument in order to return to that opening direction. Laurenz, on the other hand, just keeps going – listen to any of his orchestra’s recordings from 1940, such as “No me extraña”. This is virtuoso playing, requiring a total technical mastery of the instrument.

There are other bandoneon players whose sound we can identify. Osvaldo Ruggiero, Pugliese’s first bandoneon for 24 years, can be immediately identified by the piercing, sharp sounds he produces, for instance, in the 1944 recording of “Recuerdo” —the facility with which he dashes off the final variación makes it sound quite effortless—. One doesn’t realise how difficult it is until one hears it attempted by any other player.

Another bandoneonista with an individual sound is Minotto Di Cicco, Canaro’s first bandoneon for many years. Minotto was a real student of the instrument, producing chords with a wide spread of notes whilst always maintaining a very clean fingering. A good example of this can be found in “La muchachada del centro” from 1932.

The violins

The violin was a tango instrument from the very beginning, and there are a few orchestras which favoured the violins over the bandoneons. The classic example is the orchestra of Carlos Di Sarli. A useful listening example is the 1940 recording of the instrumental “El Pollo Ricardo”. Given the year of the recording (still in the aftermath of the D'Arienzo explosion) the playing is staccato and up-tempo, but the music is easily identified as Di Sarli from the piano playing. In the first chorus, the bandoneons are used to support the sharp attack in the string sections.

An even sharper attack can be heard from the violin of Raúl Kaplún, who joined Lucio Demare in 1942. This added strength to Demare’s lyrical sound, a combination you can hear from the opening notes of “Sorbos amargos”.

Another orchestra with a muscular violin sound, although with a denser texture, is Tanturi during his years with Campos on vocals. The classic example is “Oigo tu voz”, in which the violin opens the piece.

D'Arienzo’s violin rejects all these possibilities, and returns to the violin obligato of the guardia vieja: not really a melody, but a simple line, played low on the fourth string, which threads its way through the music. You can hear it for instance in the closing passage of his first (1937) recording of “La cumparsita” —or just about anywhere in his music—.

The piano

The use of the piano within the orchestra shows huge variation, perhaps more than with the other instruments. In some sense, it is the axis, the spine of the orchestra. Its role can be restricted to accompaniment, as in Tanturi (e.g. “Pocas palabras”), but the great orchestras did more with it. The piano often appears in the gaps between phrases, where it has different functions. Sometimes, especially in valses, it links the phrases together, e.g. Osmar Maderna’s piano for Miguel Caló in “Bajo un cielo de estrellas”. Sometimes it punctuates the phrases, as with Biagi in D'Arienzo’s orchestra, e.g. “El choclo”. D'Arienzo’s piano is usually heard quite high on the keyboard: the marcato of his bandoneons is so strong that his pianists, unusually, do not need to do much work in the bass notes.

Di Sarli’s piano is also easiest to notice in the spaces between phrases, where he places delicate, bell-like trills, but the real action is going on in his left-hand. A good example is his version of “La cachila”, and not just because it contains a rare piano solo. Di Sarli recorded this twice, in 1941 and 1952. The two versions are quite different in the piano; both are good, but Di Sarli’s growling left-hand is easier to appreciate in the second version.

Finally we come to tango’s most brilliant improvising pianist, Orlando Goñi, a man whose contribution to the Troilo orchestra has not really received the recognition it deserves. Naturally, he shines most in the instrumentals. “C.T.V.” gives you a good idea of what he is capable of: he roams all over the keyboard with great freedom. In the right hand, he can imitate and reflect the phrasing of Troilo, as in the opening notes of “La tablada”; in the left-hand (the bass notes), his legendary marcación bordoneada —striking of a chord as though rolling up through the bass strings of a guitar— provides a fluid and elastic foundation to the rhythmic drive of the orchestra that has never been equalled.

The double bass

The bass notes of the orchestra give the walking impulse, and these come from the left hand of the piano and the double bass, which had to work together in the orchestras: the double bass was usually positioned very close to the piano. Today we mostly listen to tango music on recordings, on which these notes are not as loud as they are in real life. In addition, the sound system in the average milonga does not reproduce these notes very well, so we need to make a special effort to train our ears to listen for them. Most pop music has some kind of bass drive; the tango of the golden age was simply the popular music of its day, albeit some of the most sophisticated pop music the world has ever known.

For the dancer, being aware of both the beat/rhythm and the melody, and being able to separate them in our ear, expands the range of music that we enjoy and gives us freedom. In tango music, the melody is often given a rhythmic treatment. It’s often impossible to separate them entirely, but learning to discriminate between the melody and the rhythm is one of the most important skills of all.

Adapted by the author from Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, 2nd edition, milonga press, 2014.

Michael Lavocah

Adapted by the author from Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, 2nd edition, milonga press, 2014.

http://www.milongapress.com/books/tango-stories/english/

Listening to tango dance music - A beginner’s guide

hen listening to tango music for the first time, especially if our main experience of music has been modern pop music, it can be difficult to hear what is going on, and what we hear may well seem like a “wall of sound”. The good news is that listening to music is a faculty that we can develop. Attentive listening immediately changes our experience, making it richer, creating a relationship to the music. If you are a dancer, you dance what you hear, and so what you dance will immediately begin to change as well, without learning any new steps.

1. The four elements

Dance music can be thought of as comprising four elements: beat (compás), rhythm, melody, and lyrics. Lyrics are optional, although there are always feelings. The first step in developing our listening faculty is to learn to listen to these four elements. These form four listening skills, which for the dancer will map to four dancing skills —the skills of dancing to the beat, to the rhythm, to the melody, and to the lyrics—.

Beat and rhythm are not the same. By beat we mean the regular pulse of the music. Beat alone is not music, but it is the foundation of music. We walk on the beats, and so without beat there is no walking dance. Beat is a natural, physical phenomenon, like the beat of your heart, or the cadence of walking, or breathing. Some people think of themselves as having «no sense of rhythm», but the beat is there within us, waiting to be discovered.

Beat and rhythm are connected, and it’s hard to find a tango that is pure beat (i.e. with no rhythmic variation), but there is one: Juan D'Arienzo’s “Nueve de julio” —curiously, and significantly, the breakthrough track for the new D’Arienzo sound— that was created by the arrival of Rodolfo Biagi in 1935.

By rhythm, as distinct from beat, we mean the changing pattern of the beats. A classic example is the opening of “Milongueando en el cuarenta”, recorded by Aníbal Troilo in 1941, with its tumbling syncopation: 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2, 1.

Orquesta Troilo

The melody is what we sing to ourselves, or to others, when we recall a song: the tune. The more romantic orchestras prioritise the melody over the beat and the rhythm. This is something we hear developing in the later recordings of Di Sarli. For an earlier example, we can turn to Lucio Demare’s iconic 1942 recording of “Malena”, his own composition. The melodic line is vigorous and clear, and thus easy to follow.

Finally we have the lyrics – meaning. This element is hidden if we don’t speak Spanish. As an example, let’s take Ada Falcón’s 1940 recording of “Te quiero” (“I love you”) with the orchestra of Francisco Canaro. The opening lines run:

I love you!

As no-one has ever loved you,

and no-one ever will;

I adore you!

As one adores the woman

one has to love…

Hearing these words is sure to change your relationship to the song, and to arouse feelings, perhaps memories, which can then become enfolded into the music and expressed in your dancing.

The tango orchestras mix and prioritise these elements differently and this is one way to feel the orchestras and to distinguish them.

The beat

Beats are not all the same —they have their qualities—, and each orchestra has a different quality to its beat. A first attempt to discern and feel these qualities would be to classify them into polar opposites: hard or soft, strong or weak, sharp and choppy (staccato) or rounded and smooth (legato). D’Arienzo’s beat is staccato, a development that reaches its zenith with Biagi (e.g. the extreme beat of “Racing Club”); whilst Caló’s beat is smooth and soft (“Al compás del corazón (Late un corazón)”). Troilo is more sophisticated, moving between staccato and legato (“Milongueando en el cuarenta”, 1941).

This analysis breaks down when one starts listening to music from before the golden decade. The beats of Roberto Firpo (“La eterna milonga [b]”, 1929) or Juan Maglio (“Sábado ingles”, 1928) are strong, but also soft. In this period, most of the orchestras made a prominent use of the arrastre in their music. Now, what is the arrastre? It is when the beat, instead of being something instantaneous, is made longer, starting quietly and accelerating to a crescendo. In tango, this is described by the sound zhum (written: yum). This effect can be produced on all the instruments within the orchestra. In the bandoneon, it is produced by keying the note before opening the bellows, and then accelerating the opening to a sudden stop: listen for instance to the opening of “Melancólico”. In the strings, the bow is placed on the string before it is moved, and then accelerated. If you are not used to listening for this, it’s easiest to start with the double bass rather than the violins, for instance in the opening of Piazzolla’s “Buenos Aires hora cero”. From the point of view of walking, the most important of the string instruments is the double bass, because it’s the low notes which produce the beats upon which we walk. When going on to listen to the violins, the opening chord of Di Sarli’s “Retirao” provides an exaggerated example.

When the whole orchestra joins in, the effect can be dramatic. My favourite example is a recording by Osvaldo Fresedo’s sextet, “Mamá… cuco” (1927). This reveals another side to Fresedo, full of bite. The arrastre would not be so prominent again until Osvaldo Pugliese incorporated it into what he called la yum-ba: the repeated cell of two strong arrastres (‘yum’) on beats 1 and 3, separated by a less powerful chord on beats 2 and 4 (‘ba’), supported by the double bass powerfully striking the strings with the bow.

The qualities of the beat will affect the quality of the walk. Dancing to different orchestras is not principally about choosing different figures for different kinds of music, although we might: it is about manner. The different qualities of beat inspire different qualities of walking —different ways to place out feet upon the floor—. The arrastre in particular can have a big impact on the way the weight is transferred across the foot.

Rhythm and syncopation

The main rhythmic devices in tango are syncopations —beats falling in unexpected places—.

Let’s start with D’Arienzo. Principally, he uses the syncopa, tango’s classic syncopation – in Western terms, the behind-the-beat syncopation: listen for instance to the first syncopations in “Don Juan (El taita del barrio)” (1936). For a dancer, the staccato acceleration of the syncopa is strongly suggestive of a corte, a cut step. These syncopations often occur in bursts of three —useful information for the dancer—.

Listen closely, and you’ll hear that each syncopation is actually a double syncopation – a behind-the beat syncopation followed by a different one, a before-the-beat syncopation. This is normally much quieter, so we don’t notice it, but when equal prominence is given to both, the result can be disconcerting, as in the opening beats of D’Arienzo’s “Homero” (1937). You can also hear this combination at the opening of all three of Di Sarli’s recordings of “Organito de la tarde”.

Another classic syncopation is the 3-3-2 syncopation (counting 8 beats as 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2). In tango’s golden age, this is found only in the more sophisticated orchestras. Strong examples are Pedro Laurenz’s “Arrabal” (1937) and Troilo’s “Comme il faut” (1938) —both of them electrifying recordings—.

An even more sophisticated and unique example, which we might consider derived from the 3-3-2, is the tumbling syncopation that Troilo employs at the opening of “Milongueando en el cuarenta” (1941). Counting it out, we find that it runs: 3-3-3-3-2-2-1.

The melody

Melody is constructed in phrases, just like human speech. Phrases can be short or long. In the very early days of tango, the days of the 2x4, phrases were always short: think for instance of “El choclo” —but this would soon change—. The example par excellence of the long phrase in tango music occurs in Francisco De Caro’s “Flores negras” (1927), one of the most beautiful melodies ever written in tango. It’s also an excellent example of counterpoint: listen carefully to the opening phrases, and underneath the nasal tones of Julio De Caro’s cornet violin one can hear the second violin playing a completely different tune.

The lyrics

It’s beyond the scope of this essay to talk about lyrics in any depth, but it’s worth noting that in the golden decade, sad lyrics were often given a very bright treatment by the dance orchestras —just think for instance of Troilo’s “Toda mi vida” (1941)—. This creates a bittersweet quality, which is perhaps no accident. If you want to appreciate this, there is no alternative but to learn Spanish.

Mixing the four elements

Generally speaking, dance orchestras lean towards a treatment that favours either the beat and the rhythm (D'Arienzo), or the melody (late Di Sarli). When both aspects are given space, the results are very satisfying: think for instance of Ricardo Tanturi with Enrique Campos, or Ángel D'Agostino with Ángel Vargas.

2. The instruments

Having looked briefly at the way the orchestras treat the elements of beat, rhythm and melody, we can go look at the way they use the instrumental forces at their disposal: the bandoneons, the violins, and the piano. How much prominence is each section given? In the case of the bandoneons and the violins, are individual players given solos? If they are, is there something characteristic about their playing which allows us to enjoy and to identify individual musicians?

The D'Arienzo orchestra always had a terrific bandoneon section, and many pieces culminate in a variación showcasing the ability of the whole group. A classic early example, with very clear phrasing, is the variación in “Paciencia” (1937). Listen closely and you may also hear the delightful changes in rhythm (from 4 beats per note to 3) that D’Arienzo often employs in his variaciones.

The Troilo orchestra has a completely different way of using the bandoneons. Rather than featuring the whole section, Troilo’s solo playing is given space. Troilo was famous for the feeling he put into his playing, and on many occasions he makes music just on a single note: the supreme example is his solo at the end of the milonga “Del tiempo guapo”. His rather more famous solos in “La tablada” (1942) and “La cumparsita” (1944) also use very few notes, but feel more economical and modest, with a subtle, introverted feeling.

Another way of using the bandoneon is shown by fellow bandoneonista Pedro Laurenz. His orchestra makes use of running variations, in which the bandoneon doesn’t pause for breath. The bandoneon is bisonic: each button produces two different notes according to whether the instrument is being opened or closed. It’s easier to play the instrument with power when opening, because, with the help of gravity, the instrument falls open across your knee. For this reason, many players mostly play in the opening direction, and then quickly close the instrument in order to return to that opening direction. Laurenz, on the other hand, just keeps going – listen to any of his orchestra’s recordings from 1940, such as “No me extraña”. This is virtuoso playing, requiring a total technical mastery of the instrument.

There are other bandoneon players whose sound we can identify. Osvaldo Ruggiero, Pugliese’s first bandoneon for 24 years, can be immediately identified by the piercing, sharp sounds he produces, for instance, in the 1944 recording of “Recuerdo” —the facility with which he dashes off the final variación makes it sound quite effortless—. One doesn’t realise how difficult it is until one hears it attempted by any other player.

Another bandoneonista with an individual sound is Minotto Di Cicco, Canaro’s first bandoneon for many years. Minotto was a real student of the instrument, producing chords with a wide spread of notes whilst always maintaining a very clean fingering. A good example of this can be found in “La muchachada del centro” from 1932.

The violins

The violin was a tango instrument from the very beginning, and there are a few orchestras which favoured the violins over the bandoneons. The classic example is the orchestra of Carlos Di Sarli. A useful listening example is the 1940 recording of the instrumental “El Pollo Ricardo”. Given the year of the recording (still in the aftermath of the D'Arienzo explosion) the playing is staccato and up-tempo, but the music is easily identified as Di Sarli from the piano playing. In the first chorus, the bandoneons are used to support the sharp attack in the string sections.

An even sharper attack can be heard from the violin of Raúl Kaplún, who joined Lucio Demare in 1942. This added strength to Demare’s lyrical sound, a combination you can hear from the opening notes of “Sorbos amargos”.

Another orchestra with a muscular violin sound, although with a denser texture, is Tanturi during his years with Campos on vocals. The classic example is “Oigo tu voz”, in which the violin opens the piece.

D'Arienzo’s violin rejects all these possibilities, and returns to the violin obligato of the guardia vieja: not really a melody, but a simple line, played low on the fourth string, which threads its way through the music. You can hear it for instance in the closing passage of his first (1937) recording of “La cumparsita” —or just about anywhere in his music—.

The piano

The use of the piano within the orchestra shows huge variation, perhaps more than with the other instruments. In some sense, it is the axis, the spine of the orchestra. Its role can be restricted to accompaniment, as in Tanturi (e.g. “Pocas palabras”), but the great orchestras did more with it. The piano often appears in the gaps between phrases, where it has different functions. Sometimes, especially in valses, it links the phrases together, e.g. Osmar Maderna’s piano for Miguel Caló in “Bajo un cielo de estrellas”. Sometimes it punctuates the phrases, as with Biagi in D'Arienzo’s orchestra, e.g. “El choclo”. D'Arienzo’s piano is usually heard quite high on the keyboard: the marcato of his bandoneons is so strong that his pianists, unusually, do not need to do much work in the bass notes.

Di Sarli’s piano is also easiest to notice in the spaces between phrases, where he places delicate, bell-like trills, but the real action is going on in his left-hand. A good example is his version of “La cachila”, and not just because it contains a rare piano solo. Di Sarli recorded this twice, in 1941 and 1952. The two versions are quite different in the piano; both are good, but Di Sarli’s growling left-hand is easier to appreciate in the second version.

Finally we come to tango’s most brilliant improvising pianist, Orlando Goñi, a man whose contribution to the Troilo orchestra has not really received the recognition it deserves. Naturally, he shines most in the instrumentals. “C.T.V.” gives you a good idea of what he is capable of: he roams all over the keyboard with great freedom. In the right hand, he can imitate and reflect the phrasing of Troilo, as in the opening notes of “La tablada”; in the left-hand (the bass notes), his legendary marcación bordoneada —striking of a chord as though rolling up through the bass strings of a guitar— provides a fluid and elastic foundation to the rhythmic drive of the orchestra that has never been equalled.

The double bass

The bass notes of the orchestra give the walking impulse, and these come from the left hand of the piano and the double bass, which had to work together in the orchestras: the double bass was usually positioned very close to the piano. Today we mostly listen to tango music on recordings, on which these notes are not as loud as they are in real life. In addition, the sound system in the average milonga does not reproduce these notes very well, so we need to make a special effort to train our ears to listen for them. Most pop music has some kind of bass drive; the tango of the golden age was simply the popular music of its day, albeit some of the most sophisticated pop music the world has ever known.

For the dancer, being aware of both the beat/rhythm and the melody, and being able to separate them in our ear, expands the range of music that we enjoy and gives us freedom. In tango music, the melody is often given a rhythmic treatment. It’s often impossible to separate them entirely, but learning to discriminate between the melody and the rhythm is one of the most important skills of all.

Adapted by the author from Tango Stories: Musical Secrets, 2nd edition, milonga press, 2014.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

The Secret of Golden Age Tango Music

Photo by Alex.Tango.Fuego

Photo by Alex.Tango.FuegoThere is some dialog going on right now on the Tango DJ group about "We need new danceable music!" and "If you must play alternative..."

Reading the various posts, I was reminded of something I posted to El Tango back in January of this year, more or less on topic with the Tango DJ topics. It's about the crucial elements that make Golden Age Tango sound the way it does, and why it is so difficult/impossible for contemporary orchestras/musicians/groups to reproduce that sound we all love so much.

I've been wondering lately what it is that makes so many people "not" love the sounds of Golden Age Tango - perhaps the subject of another post.

As the first paragraph states, I was simply recapping others' posts, and expanding on the subject a bit...that's what the names are about...

Here it is:

To Pat's question about crucial elements that may be required to achieve the character and quality of Golden Age tango sound...recapping prior posts to help gel my own understanding...note that I am not a musician, nor have any special technical knowledge...I just know what sounds good, what moves me, and what doesn't sound good...

Critical Elements :: Interesting points made by posters [paraphrasing]

1] Zeitgeist - World/Social Context :: The time period during which the music was played...[Ron] 'Inflected' by world events and social mores of the time ... this cannot be reproduced...ever...

2] Space/Suspense :: Golden Age orchestras/musicians deliberately or unconsciously allowed for space, suspense, suspension, openness in the arrangements...versus modern orchestras/musicians (in general) not recognizing this, and hurrying the music, just as many/most dancers hurry their dance... [Tom]

3] Orchestra Dynamics :: The smaller size of orchestras today versus in the Golden Age, the larger size of orchestras and the increased number of violins and bandoneons provided a richness and depth to the sound...[Christopher, Myk] Inexperienced musicians without sufficient practice time and not enough emphasis on ensemble playing...[Christopher]

4] Subconscious Awareness :: The fact that the human mind 'knows' that this is no longer the Golden Age, and may impact how we 'hear' Golden Age vs. Modern Age tango... [Bruno] Were the listeners of the Golden Age as moved by the music then, as we are today? Who knows?

5] The Fifth Element :: Whether you ascribe to Ilene's 'magic' quality, an intangible that simply cannot be reproduced, or believe that there may be some other quintessential element, possibly metaphysical energy, which takes this 'magic' quality, and pulls in the Zeitgeist of that time. Add to the mix the emotional energy of the composers, orchestra leaders, and individual musicians - more musicians, more energy. Finally, top it off with the emotional energy of the dancers and listeners they were composing and playing for at that time. Let's just call it 'energy'. This had to be a profound influence, in my view.

I doubt that the sound and emotion of that music, from that time, can ever be reproduced. More importantly, why? Why even attempt to reproduce it? Not that Pat suggested this in the originating post, but there does seem to be a gentle undercurrent of a desire to somehow reproduce the sound. It's interesting to discuss and ponder, which I'm sure we all have, and will continue to do.

My feeling is to leave it alone. I'm not saying not to discuss or ponder it, but to let the music be what it is. Let the musicians of today create their own music - free in their own creative juices. They say "Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery", but I think in this case, it is not. There is something very beautiful about spontaneous, unhindered, free flowing creativity. Let ColorTango be, and sound like, ColorTango. Let the others be and sound like themselves. When a painter today is commissioned for a work, hopefully the patron doesn't say "make it look like a Matisse..." - the patron wants the artist to create a uniquely individual, one-of-a-kind, work of art.

One of my favorite tango quotes is by Jorge Luis Borges. He said "The tango can be debated...but it still encloses, as does all which is truthful, a secret."

Let's keep that magic, that energy, that secret...let's keep it secret...

Or, you may ascribe to the philosophy that tango is "just a dance..."

Ilene also added a comment after my post about the recording technology of the time. No doubt that played a role as well - as compared to the digital recording technology in use today. There is good, skillful, highly crafted digital recording going on today, resulting in very rich sounding recordings and then there is the not-so-good.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)